Survey module: Holy Wells

Looking for Holy Wells

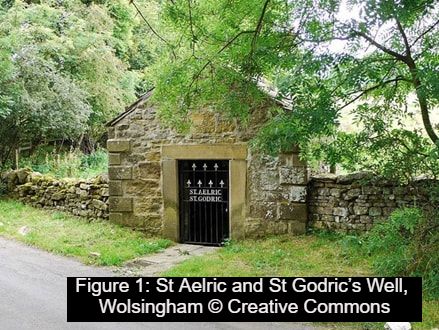

Holy wells or springs once formed an important part of the religious landscape of NE England. Some could be elaborate affairs with stone-built structures over them or carefully constructed basins or pools, others could be little more than a muddy puddle where a spring or a source of water emerged from the ground.

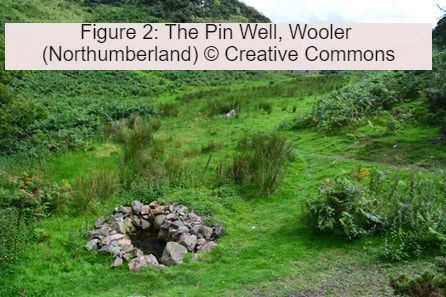

A good example of a well-built and carefully maintained holy well is that of St Aelric and St Godric at Wolsingham (County Durham) (Figure 1) and example of a less well developed is the so-called Pin Well near Wooler (Northumberland).

In Britain, the use of ritual wells and springs is best known in the medieval and early modern period. Sites could be visited simply for good luck, others were reputed for their healing powers. Sometimes, the water was simply sipped or poured on the part of body that needed healing; in other cases a small offering, such as a pin, might be left by the visitor. Sometimes in Northern England and Scotland a small rag or ribbon might be tied to a nearby tree.

Use of holy wells was a perfectly respectable part of Christian worship. Many were located close to (or even in) churchyards, and others were given Christian names (e.g. St Oswald’s Well; Our Lady’s Well). It is these names that are often an important clue when we are looking at old maps for the site of possible wells.

It is often suggested that the use of holy wells goes back to pre-Christian times. It is certainly possible that some sites may be of considerable antiquity, and we know that in prehistoric societies wells and springs were often seen has having real religious importance. Today, there has also been a revival of interest in holy wells, particularly amongst those with an interest in ‘New Age’ beliefs and neo-pagans.

Holy wells or springs once formed an important part of the religious landscape of NE England. Some could be elaborate affairs with stone-built structures over them or carefully constructed basins or pools, others could be little more than a muddy puddle where a spring or a source of water emerged from the ground.

A good example of a well-built and carefully maintained holy well is that of St Aelric and St Godric at Wolsingham (County Durham) (Figure 1) and example of a less well developed is the so-called Pin Well near Wooler (Northumberland).

In Britain, the use of ritual wells and springs is best known in the medieval and early modern period. Sites could be visited simply for good luck, others were reputed for their healing powers. Sometimes, the water was simply sipped or poured on the part of body that needed healing; in other cases a small offering, such as a pin, might be left by the visitor. Sometimes in Northern England and Scotland a small rag or ribbon might be tied to a nearby tree.

Use of holy wells was a perfectly respectable part of Christian worship. Many were located close to (or even in) churchyards, and others were given Christian names (e.g. St Oswald’s Well; Our Lady’s Well). It is these names that are often an important clue when we are looking at old maps for the site of possible wells.

It is often suggested that the use of holy wells goes back to pre-Christian times. It is certainly possible that some sites may be of considerable antiquity, and we know that in prehistoric societies wells and springs were often seen has having real religious importance. Today, there has also been a revival of interest in holy wells, particularly amongst those with an interest in ‘New Age’ beliefs and neo-pagans.

In Britain, the use of ritual wells and springs is best known in the medieval and early modern period. Sites could be visited simply for good luck, others were reputed for their healing powers. Sometimes, the water was simply sipped or poured on the part of body that needed healing; in other cases a small offering, such as a pin, might be left by the visitor. Sometimes in Northern England and Scotland a small rag or ribbon might be tied to a nearby tree.

Use of holy wells was a perfectly respectable part of Christian worship. Many were located close to (or even in) churchyards, and others were given Christian names (e.g. St Oswald’s Well; Our Lady’s Well). It is these names that are often an important clue when we are looking at old maps for the site of possible wells.

It is often suggested that the use of holy wells goes back to pre-Christian times. It is certainly possible that some sites may be of considerable antiquity, and we know that in prehistoric societies wells and springs were often seen has having real religious importance. Today, there has also been a revival of interest in holy wells, particularly amongst those with an interest in ‘New Age’ beliefs and neo-pagans.

What to look for on maps:

The first source of evidence we are going to be using for the project is historical maps. We will start by surveying all the past Ordnance Survey maps. These maps were first produced in the mid-19th century and provide a coverage of the entire country, although we are going to begin by focusing in on just the old County Durham (roughly between the Tyne and the Tees).

These maps are often very detailed and include a lot of information – including noting the location of a range of springs, wells and fountains. So what are we going to look for? The main evidence we can use is local place names (the technical term is toponyms).

The most obvious placename to look for is not surprisingly ‘Holywell’ – there are often variants to this spelling e.g. Hollywell, Halliwell, Hallywell etc). Sometimes the name is related to an actual well, but sometimes it is given to a nearby building (eg. Hollywell House) or a natural feature (e.g. Holywell Burn). All these need to be included.

Another clue is a well or spring with a religious name, such as saints’ name (St Oswald’s Well; St Mary’s Well) or another religious term (e.g. Our Lady’s Well; Lady Well). Sometimes there are more unusual terms. We’ve already seen a picture of Pin Well near Wooler, but terms such as Rattling Well, Roaring Well. The well might even be given a name associated with a legendary figure (for example, there is a King Arthur’s Well, near Greenhead, Northumberland and a Robin Hood’s Well, Chollerford, Northumberland).

Basically, if a well or spring has an interesting, unusual or intriguing name- it needs recording. If in doubt, check with David Petts or record it anyway. The details of how to record these sites can be found here.

What next?

Once we’ve completed an initial survey of the Ordnance Survey maps we should then have an initial list of possible holy and healing wells. The next job will be to do more research on them. This will include

Obviously are precise plans will have to be flexible to accommodate the impact of the coronavirus – but we’ll certainly be able to record and share all the information we find

More reading

If you want to read more about holy wells there are lots of helpful resources on the internet

A good start is the Wikipedia article on holy wells: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_well

Another great read is the In Search of Holy Wells and Healing Springs blog [https://insearchofholywellsandhealingsprings.com/] which has lots of information including old versions of the Source and Living Spring journals.

I’ll also try to scan in and add digital copies of other article about holy wells and add them to the website.

Use of holy wells was a perfectly respectable part of Christian worship. Many were located close to (or even in) churchyards, and others were given Christian names (e.g. St Oswald’s Well; Our Lady’s Well). It is these names that are often an important clue when we are looking at old maps for the site of possible wells.

It is often suggested that the use of holy wells goes back to pre-Christian times. It is certainly possible that some sites may be of considerable antiquity, and we know that in prehistoric societies wells and springs were often seen has having real religious importance. Today, there has also been a revival of interest in holy wells, particularly amongst those with an interest in ‘New Age’ beliefs and neo-pagans.

What to look for on maps:

The first source of evidence we are going to be using for the project is historical maps. We will start by surveying all the past Ordnance Survey maps. These maps were first produced in the mid-19th century and provide a coverage of the entire country, although we are going to begin by focusing in on just the old County Durham (roughly between the Tyne and the Tees).

These maps are often very detailed and include a lot of information – including noting the location of a range of springs, wells and fountains. So what are we going to look for? The main evidence we can use is local place names (the technical term is toponyms).

The most obvious placename to look for is not surprisingly ‘Holywell’ – there are often variants to this spelling e.g. Hollywell, Halliwell, Hallywell etc). Sometimes the name is related to an actual well, but sometimes it is given to a nearby building (eg. Hollywell House) or a natural feature (e.g. Holywell Burn). All these need to be included.

Another clue is a well or spring with a religious name, such as saints’ name (St Oswald’s Well; St Mary’s Well) or another religious term (e.g. Our Lady’s Well; Lady Well). Sometimes there are more unusual terms. We’ve already seen a picture of Pin Well near Wooler, but terms such as Rattling Well, Roaring Well. The well might even be given a name associated with a legendary figure (for example, there is a King Arthur’s Well, near Greenhead, Northumberland and a Robin Hood’s Well, Chollerford, Northumberland).

Basically, if a well or spring has an interesting, unusual or intriguing name- it needs recording. If in doubt, check with David Petts or record it anyway. The details of how to record these sites can be found here.

What next?

Once we’ve completed an initial survey of the Ordnance Survey maps we should then have an initial list of possible holy and healing wells. The next job will be to do more research on them. This will include

- Looking on older maps to see if they are marked or if the names have changed over time

- Visiting the sites where possible to see if anything survives

- Possibly recording any remains we identify.

- We’ll also create a map to show all this information.

Obviously are precise plans will have to be flexible to accommodate the impact of the coronavirus – but we’ll certainly be able to record and share all the information we find

More reading

If you want to read more about holy wells there are lots of helpful resources on the internet

A good start is the Wikipedia article on holy wells: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_well

Another great read is the In Search of Holy Wells and Healing Springs blog [https://insearchofholywellsandhealingsprings.com/] which has lots of information including old versions of the Source and Living Spring journals.

I’ll also try to scan in and add digital copies of other article about holy wells and add them to the website.